On Ferris Bueller and Benito Mussolini

.

As should be clear, Ferris Bueller and Benito Mussolini have a lot in common.

Now, at first it might be hard for many to see it: Ferris Bueller is a fictional Chicago teenager in a beloved 1980s comedy film, while Benito Mussolini was a cruel, often murderous dictator who dragged his country into both stumbling imperial conquest and a disastrous world war. But this, the enlightened academic already knows, is just where their similarities begin.

At first glance, Ferris Bueller might seem like your average runaway trickster god—an Illinois Loki, the Eshu of the elevated trains. This is natural: the habits of such deities are well-established. They use their intelligence to deceive others, achieve their goals, form chaos to bring about order as they see it. Their morality is ambiguous, their argus-eyed narcissism keeping all around them on their toes. They hide their smarts to dumbfound all the dumb mortals they can find, and use their magnificent power to right wrongs either preexisting of their own invention.

This also describes most fascist dictators.

Ferris Bueller has a great deal in common with the great baddies of the last century: most notably, meddling unrequested in the lives of others, vague omnipotence, and a startling lack of knowledge, in his case due to truancy, on how tariffs work. The world so thoroughly revolves around Ferris Bueller that he is, in fact, named after a wheel; Mussolini so completely conquered his Italian era that the calendar restarted its count of years from his assumption of power.

There’s the obvious synergies—both love interrogating minorities (“Do you speak English?,” Ferris snottily asks a garage attendant, who replies “Uh, what country do you think this is?”) and their ability to fake ill health—Ferris fakes stomach cramps to get out of school, while Mussolini wore a comically large bandage over his superficial wound after an assassination attempt. Both had deeply unfortunate effects on their friends: Mussolini passed laws that drove his long-time companion Margherita Sarfatti into exile, while Ferris absolutely caused his best friend to total his dad’s absolutely totally sweet, can-you-believe-it Ferrari Spyder.

Neither were terribly concerned about this.

And, as everyone knows, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off takes place on June 5—the same day that Mussolini entered Italy into its ill-starred, world-war-causing alliance with Adolf Hitler. Coincidence? No chance.

Mussolini’s power is, like Bueller’s, rooted in his complete immunity from the mundane. Both of their parents are somehow secondary characters in their own lives: Mr. Bueller works at the paper factory and raises his family, but you can barely remember his name or face. Benito’s father, whatshisname, was a blacksmith similarly relegated to the dustbin of history. We mere mortals have families; they have side characters. And both families raise sons who, in public perception, do nothing normal: it is improbable that the fictional Mussolini presented to the public, like the Ferris of movies, ever went to the bathroom, eats a snack, gets sick. There is no time for anything else, in the pursuit of boundless power.

In fact, it would be fair to say that Benito Mussolini aspired to be Ferris Bueller. Mussolini, the biggest ape in apedom, shared with Ferris the ability to just…do things through sheer force of will. Ferris somehow talks his way into restaurants he can’t afford, out of a school he barely attends, into the heart of a woman who could surely do better, and somehow into a place at the head of the city’s largest parade and some form of uncrowned kingdom over the forcemeats of America’s third largest metropolis. He does all of this in spite of no qualifications of any kind.

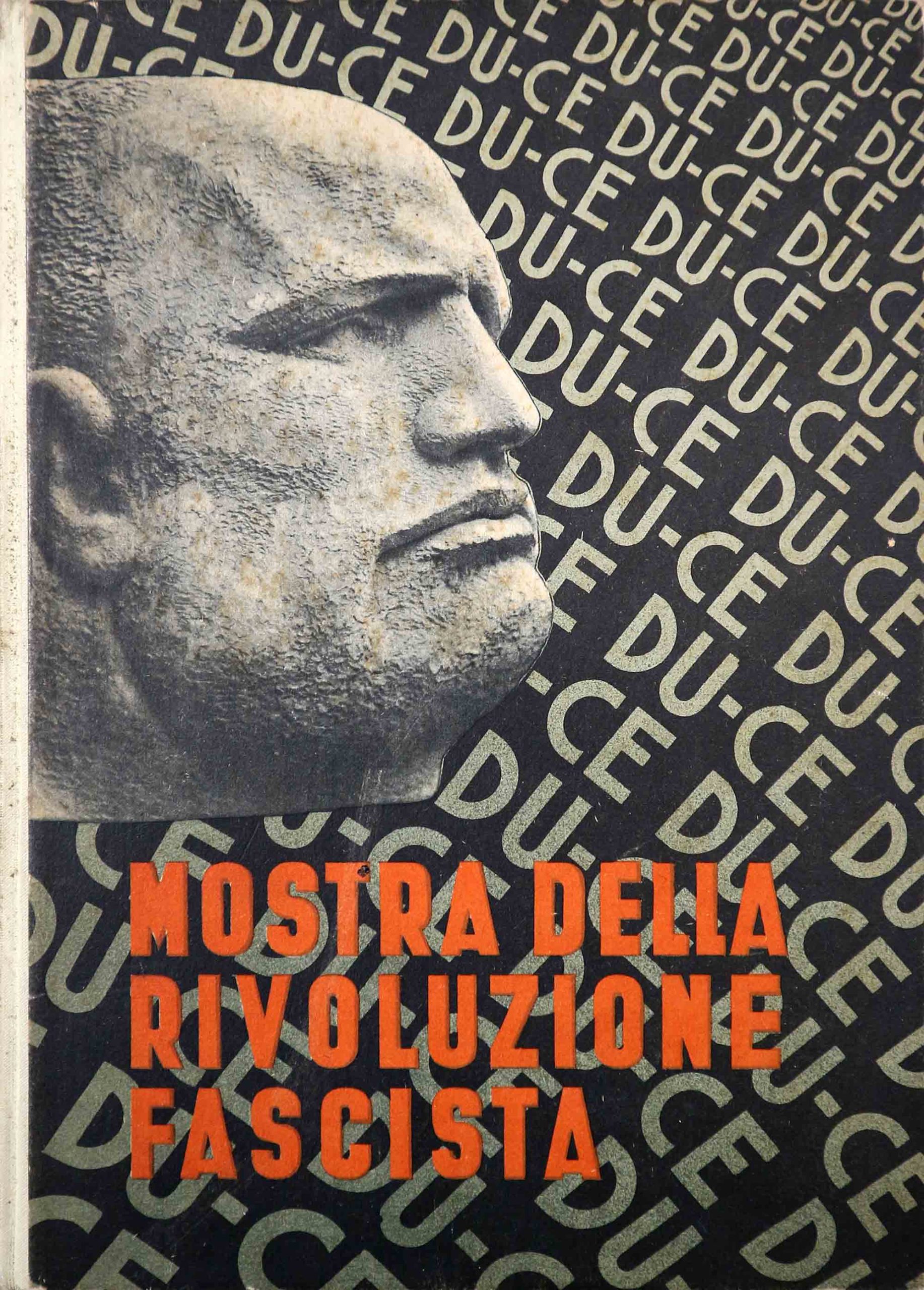

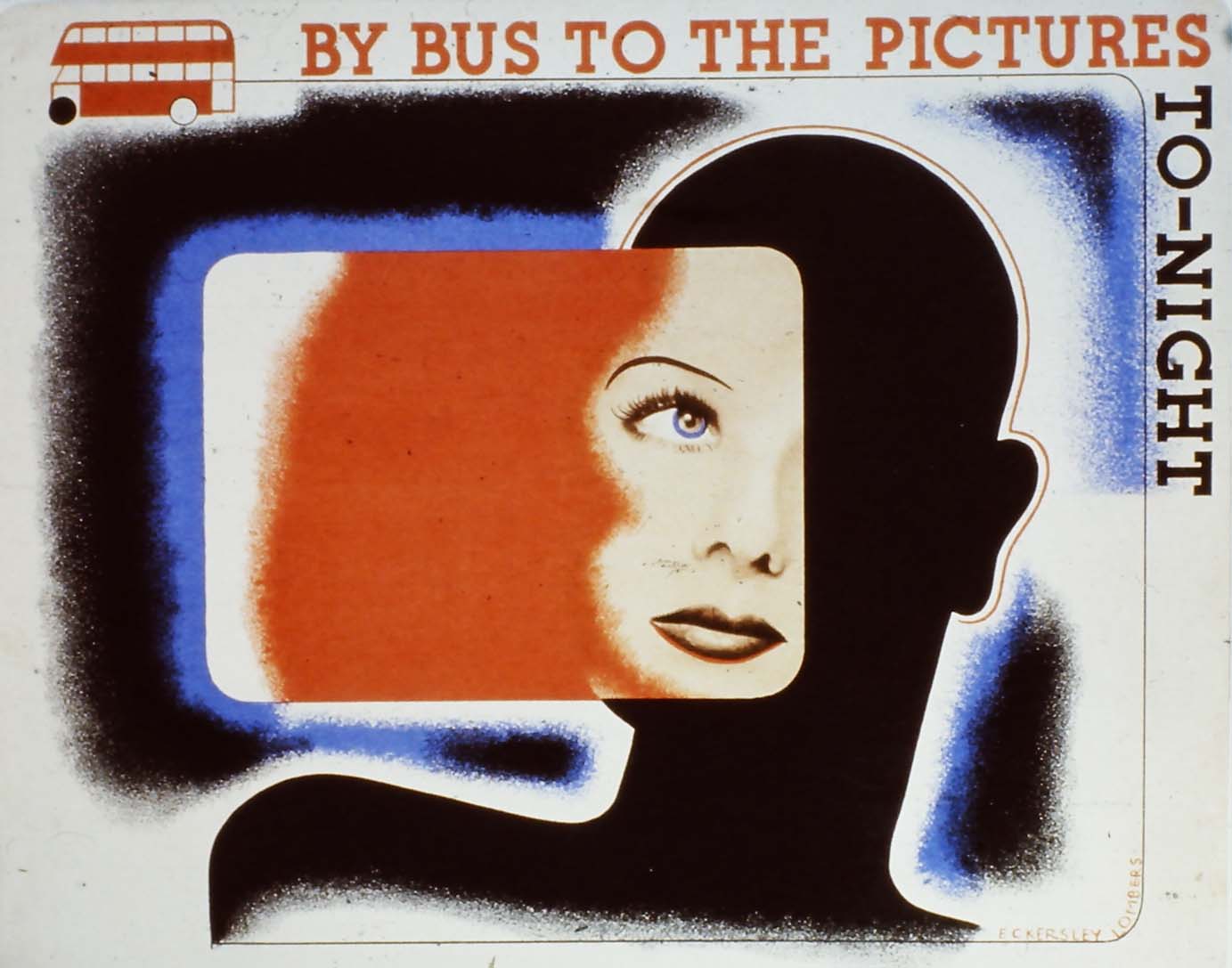

Ferris halfway through his story | Mussolini halfway through his.

Mussolini, in his turn, was an elementary school teacher who took over one of the world’s most troubled regions by simply…showing up and saying he could. Kings cowered before him; statesmen politely stepped aside. When asked the year before his seizure of the Italian government what programs he would have for Italy, the best he could muster was “my program is—I plan to govern.” A year later he was, however improbably, the dictator of the whole peninsula—life moves pretty fast. If you don’t stop and look around once in a while, you could miss it.

Ferris, too, had no plan other than “to govern”—like Mussolini, he’s a smarmy brat who changes the lives of everything he touches. “I can’t handle anything,” his best friend Cameron asserts: “school, parents, the future. Ferris can do anything.” The anything that Ferris proceeds to do is bust his friend and girlfriend out of school so that they can engage in an implausibly full day that, in fact, spills the banks of time itself: he somehow simultaneously goes to lunch, goes to a baseball game, and goes to the art museum in one day’s short hours, and most importantly is so powerful that, like Mussolini, he can magically flick his wrist and reschedule the Von Steuben Day Parade from late September to the early days of June and then become its chief cheerleader, band director, and head steward all in one. Like Benito, Ferris does not bend to The State; The State bends to him.

Ferris and Benito meeting admirers outside government-run facilities.

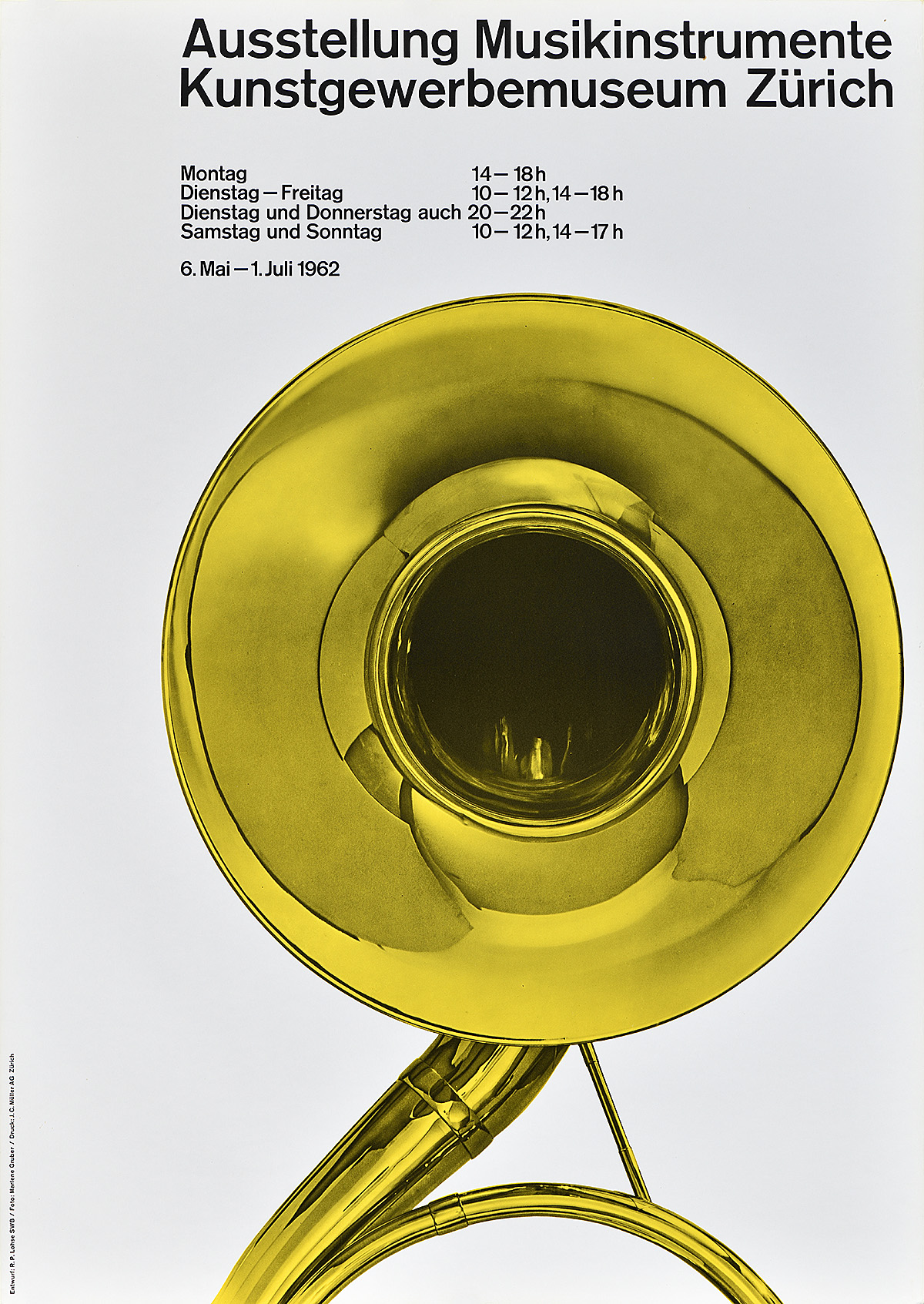

Most importantly Mussolini, like Ferris Bueller, understood that you can use contemporary art to further your goals. Benito, as we show in our ongoing exhibition The Future Was Then, was himself inspired heavily by futurist artists—whose love of absurdity might lead to poetry involving shouting, paintings of nothing at all, performative cookbook recipes that don’t make sense, or even blog posts asserting that 1930s dictators and American movie characters are linked—but Ferris Bueller, too, took his cues from the arts. Bueller, the very moment he has smuggled Sloane and Cameron away from their real world, takes them right to an art museum. As low-key Reagan-era synthesizer music plays over the scene, the three stand present in quiet contemplation in front of an unseen canvas that may, in fact, be We the Viewers ourselves. The three are contemplating us—in our bizarre democracy—while themselves unburdened by it.

Ferris and friends at the Art Institute of Chicago | Mussolini and friends at the Galleria Borghese in Rome

The mere application of bread and circus, for both men, works. A good meal and a trip to the art museum sponsored by The Leader is enough to inspire his followers: “Seventeen years and I’ve never taken a stand,” Cameron declares. “Now, I’m gonna do it. I’m taking a stand against my father, against my family, against myself, against my past, my present and my future.” Like Benito, Ferris can drive his frenzied followers in open revolt against their existing systems.

Where Mussolini’s desire to become Ferris must be most obvious: success. Ferris Bueller, for all his monkey business, never faces a repercussion: he keeps all his friends, fails to get arrested, makes off with the girl, and somehow earns back the love of his exasperated, bedeviled sister. At their respective nadirs, Mussolini ended up dangling from a gas station while Ferris Bueller ended up at a Chicago Cubs game which, even the most bedraggled Cubs fan might be obliged to admit, is a better outcome.

And in the end, Ferris is just as pragmatic. Facing his followers at the cusp of their errant day of triumph, he tells them, and us, what we’re in for:

The question isn’t what are we going to do? Ferris, like Mussolini, ponders into the humbled static of his world. The question is: what aren’t we?