Two Posters by Leonetto Cappiello: Cigarettes, Seduction, & an Elephant

.This post is part of a new series dedicated to looking at posters within the museum’s permanent collection.

Cigarettes have never been my vice. But while I was working on the catalog of the Poster House collection recently, I was captivated by two of the smoking-related images by the great Italian designer Leonetto Cappiello (1875–1942). His grand reputation as “the father of modern advertising” was established precisely by designs like these, in which he moved away from the romantic, painterly posters of such acclaimed predecessors of the Belle Époque as Jules Chéret. Instead, this untrained artist introduced boldly colored, simpler, more graphic forms appropriate to the burgeoning modernism of the city of Paris. Cappiello had begun to work there in 1897 as a caricaturist, producing illustrations for such well-known journals as L’Assiette au Buerre and La Revue Blanche—a training in both graphic design and irreverence that evidently served him well later. His career as a poster designer took off in 1900, when he signed a contract with the Parisian advertising agent and printer Pierre Vercasson.

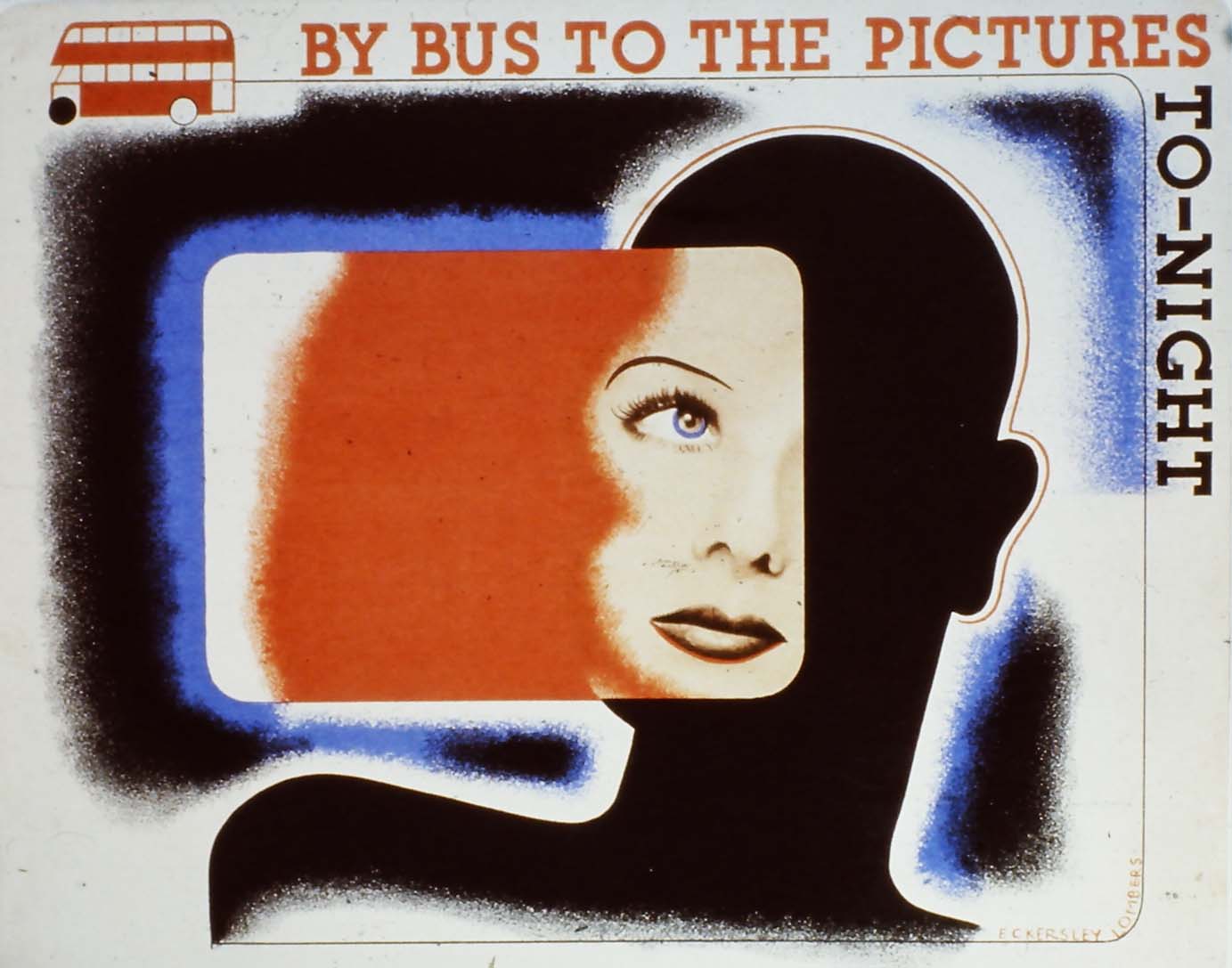

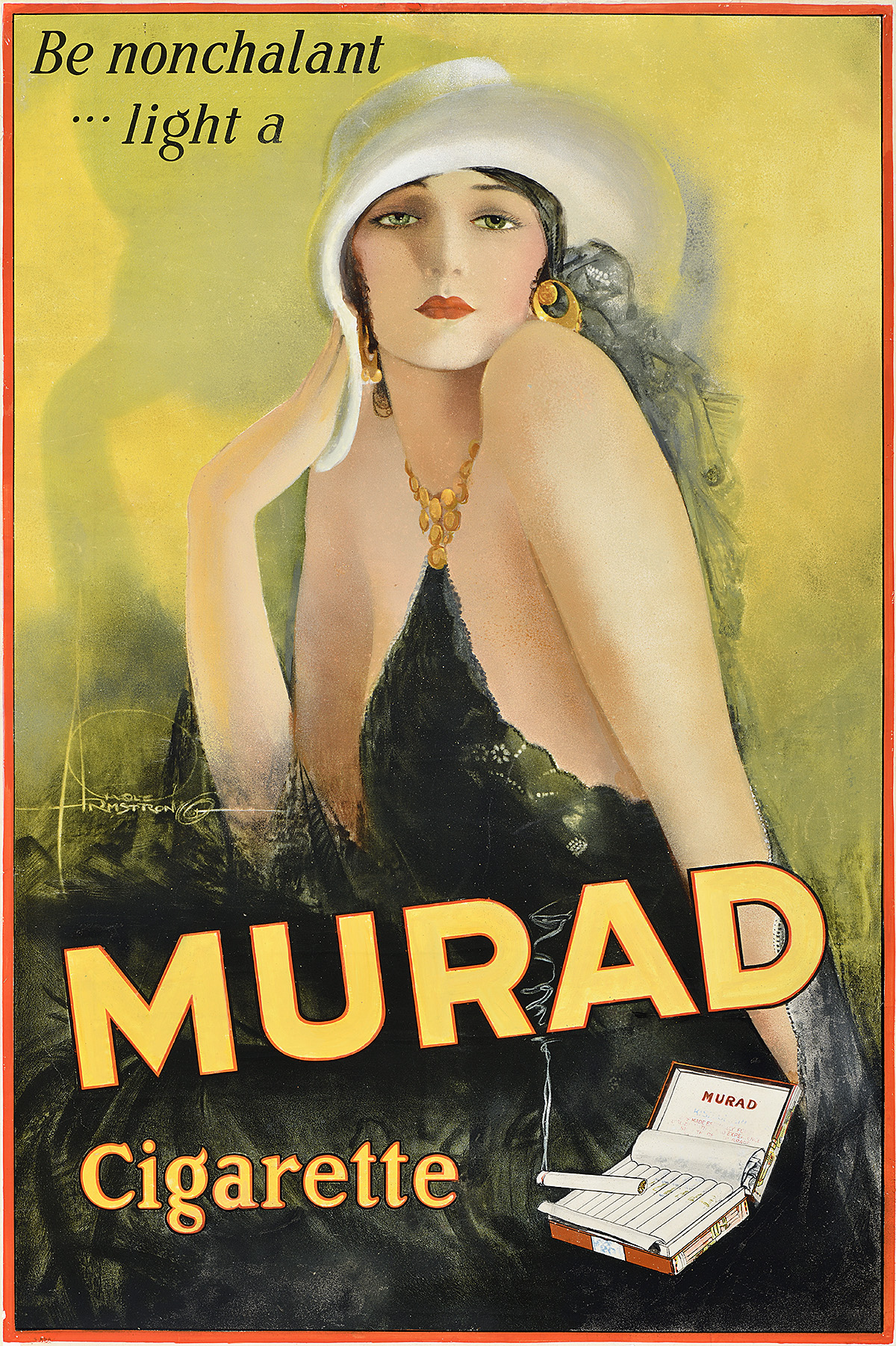

Murad (c. 1925) by Rolf Armstrong

Posters promoting cigarettes and their accoutrements are not exactly unusual; but during the early decades of the 20th century, when Cappiello produced his designs (and for decades beyond), this kind of advertising was most commonly focused on a rather obvious seductress in a languorous pose, or on a sophisticated-looking couple exchanging mildly salacious repartee in an accompanying caption. This poster from the museum’s collection by American designer Rolf Armstrong, encouraging the viewer to “Be nonchalant…light a MURAD cigarette” (1925) perfectly exemplifies such conventions. (The hand-rolled Murad cigarettes were first produced in New York in the early 20th century and point to the expanding taste for pure Turkish tobacco. Early posters and cigarette cards for the brand, like quite a few others, typically emphasized its Eastern roots, with figures dressed in Turkish-style clothing in “exotic” settings. But by 1925, Murad’s image was more closely aligned with the styles seen in mainstream American film and fashion.) Cigarettes were also hawked in these posters by movie stars, sportsmen, and other obviously “manly” men—and physicians. And the relationship between cigarette smoking, eroticism, and glamour, was, of course, embedded most inexorably in the popular consciousness by countless now-classic movies of the first half of the century. (My favorite remains the final scene from the great weepie, Now Voyager [1942], with Paul Henreid and Bette Davis—“Shall we just have a cigarette on it?”)

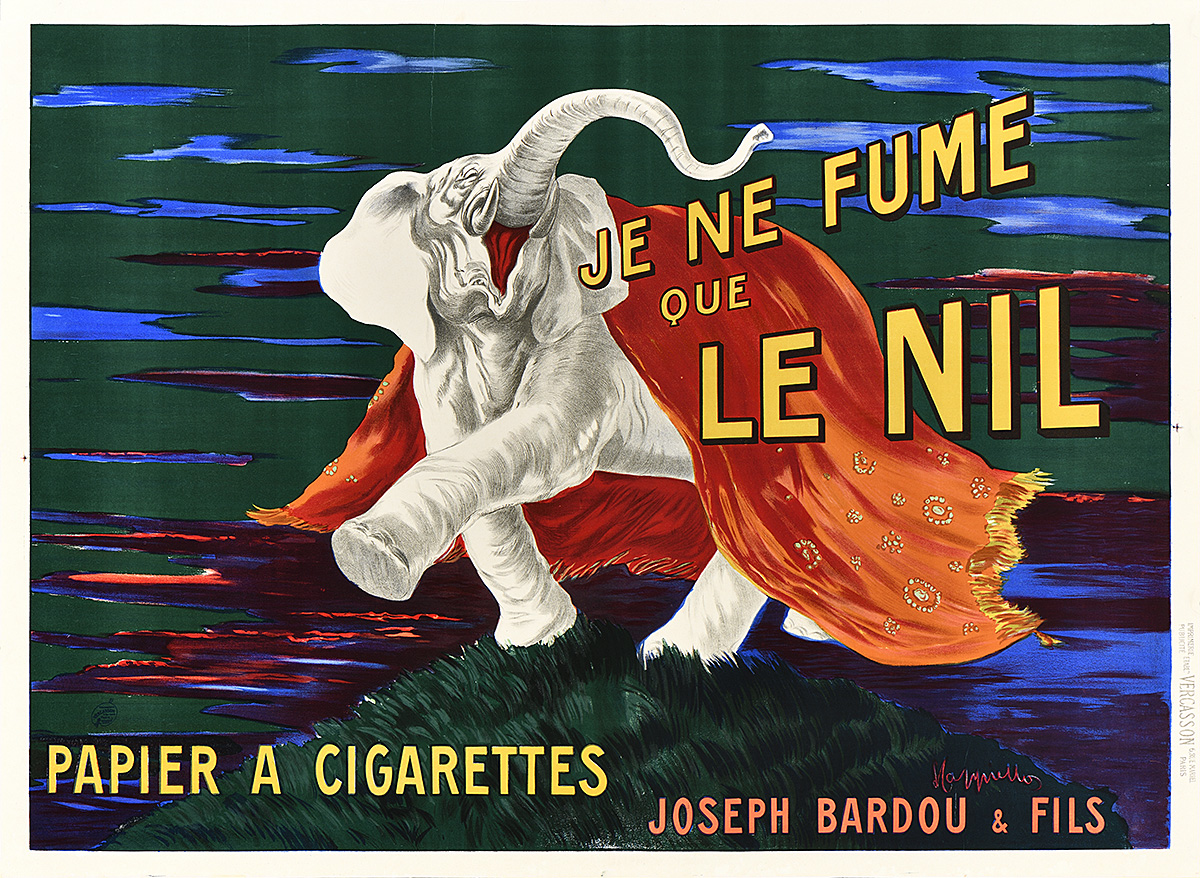

Le Nil (1912) by Leonetto Cappiello

It must be said that my first encounter with Cappiello’s 1912 poster, dominated by a trumpeting elephant sporting a regal red-and-gold cloak as it lumbers along the Nile, did not immediately suggest either seduction or sophisticated glamour—or even cigarettes for that matter. Only the slogan “Je ne fume que Le Nil” (I only smoke Le Nil) emanating from the animal’s mouth revealed that the hulking beast was the mascot for the Le Nil brand of cigarette rolling papers. It’s difficult to comprehend the precise appeal of a cigarette-smoking elephant but given that the creature became even more successful for the brand after Cappiello’s redesign of 1912, he clearly knew what he was doing here. (Another version of this image incorporates the slogan “Le fumeur avisé ne fume que Le Nil” [The astute smoker only smokes Le Nil].) In the 1870s, Joseph Bardou, an esteemed manufacturer of cigarette rolling papers based in Perpignan in southern France, whose name appears on the poster at lower right, had begun exporting to the Middle East, and to Egypt in particular. The “Le Nil” line was officially launched in 1887 for this market and to provide European consumers, gripped by “Orientalism” in many guises, with a convenient way of wrapping their “tabac levantin” or Turkish tobacco. (In addition to the celebrated elephant, the promotional images for the product also included such popular Egyptian motifs as sphinxes and pyramids.) Notably, Cappiello worked with Vercasson until the outbreak of war in 1914, and the firm remains best known for its work with him.

Cachou Lajaunie (1920) by Leonetto Cappiello

In the second poster, published in 1920, soon after Cappiello had begun a collaboration with the publisher Édouard Devambez (who, by this time, had established a serious reputation for the publication of fine prints, books, and posters), he similarly set an eye-catching motif against a dark ground, creating a compelling context for a decidedly mundane commodity. And again, the advertised product is not immediately obvious from the image alone. The elegant woman with a bouffant, wearing an elaborate dress composed of colorful leaves (possibly stripped from an entire tree) as she languidly exhales the smoke from a cigarette in her right hand, initially appears to be a distinctively bold and brilliant version of the alluring-female-with-cigarette prototype. But the tiny, yellow tin just visible in her left hand is actually the product she promotes with somewhat excessive nonchalance. For this is one of several posters designed by Cappiello for Cachou Lajaunie, black pastilles intended both for digestion and to freshen the breath—presumably the major concern of smokers at the time. The pastilles were originally developed in Toulouse, France in 1880 by a modest pharmacist named Léon Lajaunie and sold to his customers, who apparently included chauffeurs and cyclists (we will probably never know why the breath of these particular constituents was so very nasty) as well as smokers. These licorice-flavored pastilles have nonetheless survived their obscure origins and are still available in France today. While the same cannot be said of Le Nil rolling papers, which met their end by 1970, their representative cigarette-smoking pachyderm, like the leafy lady promoting breath pastilles, remains a monument to Cappiello’s inventive and undeniably peculiar artistic sensibility.