You Depend on Us: A Close Look at a Poster

.Everyone who gives Poster House tours is encouraged to do so in their own style. We are discussing the same art and design, dealing with the same material, yet we tie in our own histories and interests to each show. When preparing my tours for a new batch of exhibitions, I will first read and discuss the curator’s notes with them, and, if possible, talk to the artists who created the work. Only then do I focus on the posters or the art that speaks to me.

Last autumn, Poster House opened Masked Vigilantes on Silent Motorbikes, an exhibition of works of art made out of street posters. The show could be viewed as an exhibition of non-sponsored public art, with many of the pieces having a socially-targeted function that questions the role of advertising. Many of the works reflect criticisms of modern-day social media made physical.

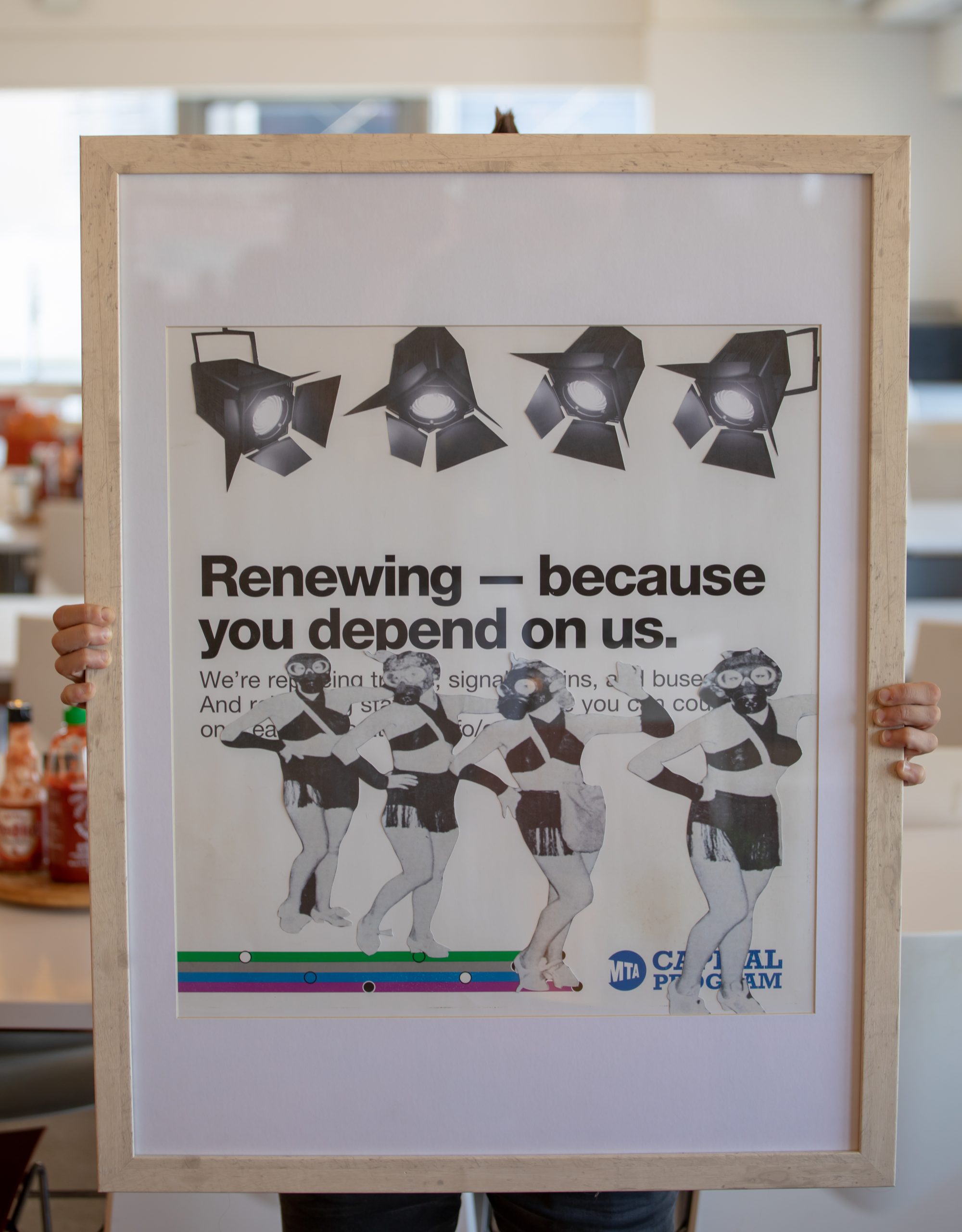

While walking through the gallery, I was particularly drawn to a small black-and-white piece by Jilly Ballistic sandwiched between large, vibrantly colorful works by KAWS and Michael de Feo. Jilly’s art is often politically charged with an anticapitalist, anticonsumerist narrative. Her name itself is a pseudonym—a sensible choice as she has been labeled New York’s “leading subway vandal.” A key difference between the posters we usually highlight and this exhibition of poster-based art is that the best poster messaging is unambiguous, direct, and clear. Jilly’s piece, however, asks questions—and I wanted to understand more.

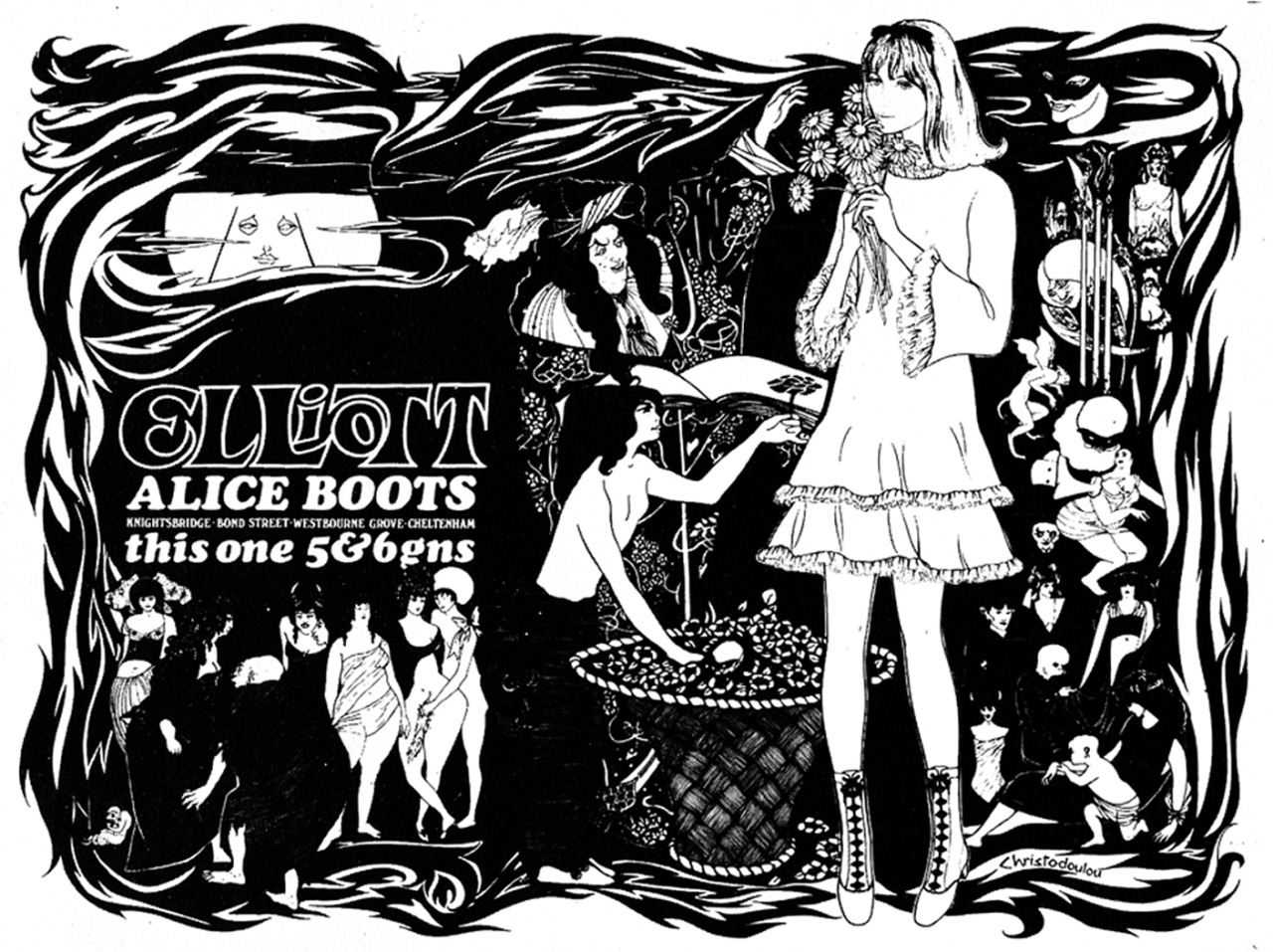

Renewing Because You Depend On Us, Jilly Ballistic, c. 2010

Image c/o the artist

The composition shows a group of British female performers from the 1940s known as the Windmill Girls. They are overlaid on top of a poster announcing a New York Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA) capital spending program. Although I am personally interested in art history, I am more fascinated by art as history—and Jilly’s piece references a little-known snippet of World War II-era history that I came across while curating a recent exhibition on the topic.

The British have a concept of “national treasures”—people that break into the cultural consciousness and transcend barriers, frequently by being relatable, using charm and self-deprecating humor even when aspects of their lives may be outside the mainstream. Present day examples could include Eddie Izzard, Stormzy, and Tracey Emin. The Windmill Girls became national treasures during the Second World War.

At the outset of the War, the government unit that would become responsible for all British propaganda had identified resilience and humor as key national characteristics to be amplified in order to achieve the best public response. In 1940, when the Nazi bombing of London started, there were 42 theaters operational in the city. Within a few months, only one remained: the Windmill Theater. Prior to the War, this establishment had been controversial. In addition to the usual revue fare of comedians and dancers, some of the female performers posed nude and motionless on stage behind strategically placed fans. The theater’s motto was, “if you move, it’s rude”—playfully acknowledging and skirting a high court ruling that naked women could not appear on stage. Motionless women, however, were similar enough to nude statues in a museum that they were deemed “not obscene or morally objectionable.”

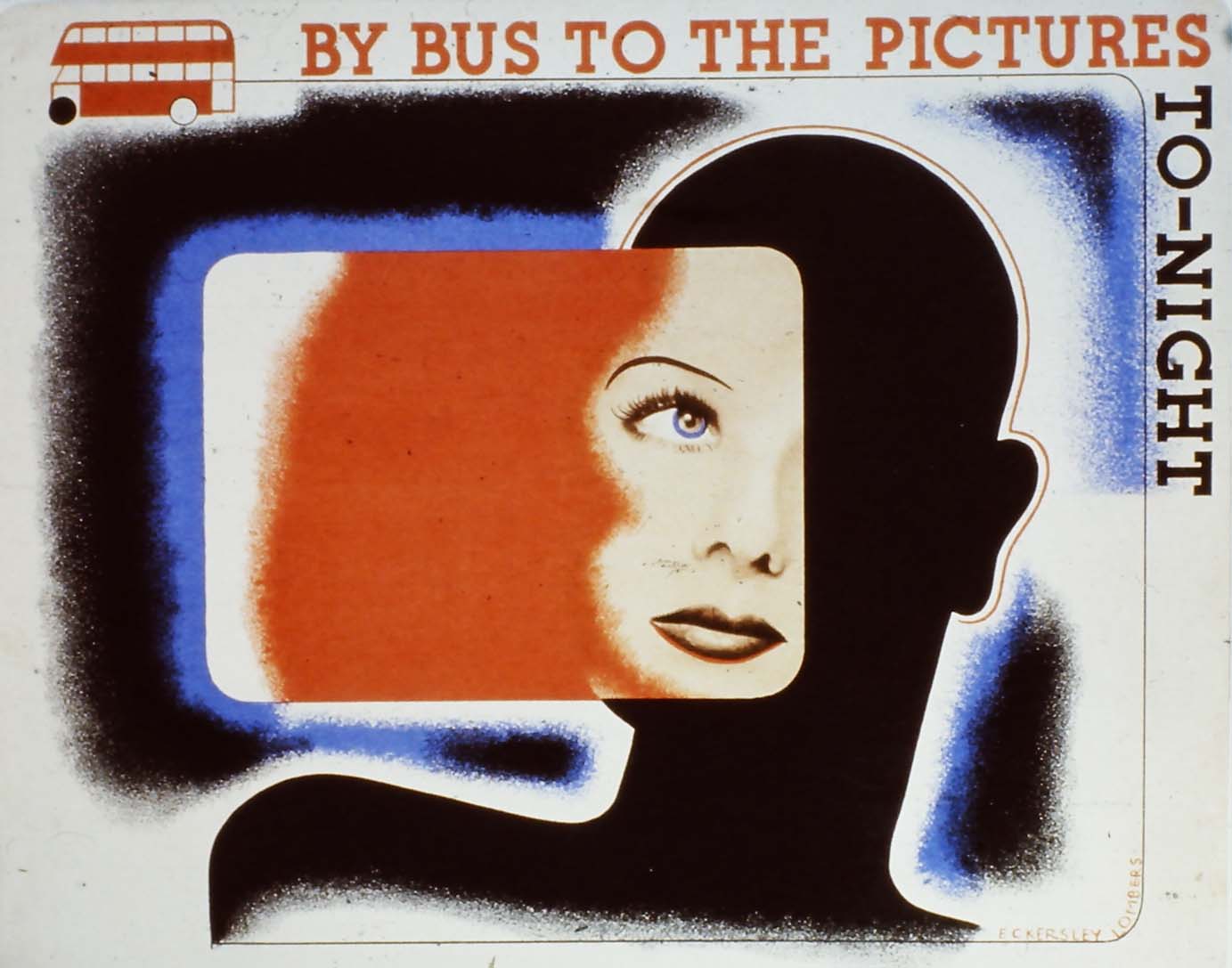

Photograph of The Windmill Girls

Image c/o F Yeah History

The War changed the controversy around these performers. As the last form of live theatrical entertainment in London, these young women became heroes to many as they provided precisely the type of stalwart resistance to terror that the UK Ministry of Information was trying to promote. Nightlife, laughter, and fun was officially seen as an antidote to the totalitarian horror across the Channel. While the danger was certainly real and many people working in and around the theater died, the Windmill stayed open to provide hundreds of free tickets to soldiers every week.

In addition to incorporating historic imagery into her work, Jilly Ballistic frequently superimposes gas masks onto her figures as an anti-militarism statement. In the case of the Windmill Girls, though, this was not necessary, as they often posed for publicity photographs while dancing in gas masks. An irreverent gesture to the actual dangers of performing during the Blitz, such accessories were as humorous as they were practical.

The real magic in Jilly’s piece, however, comes from the combination of the historic imagery with the MTA’s tagline text “renewing-because you depend on us.” While the MTA uses this phrase as a justification for the minor inconvenience of various subway closures and delays, it takes on new meaning when accompanying these intrepid performers. Suddenly, it is a feminist declaration, a recognition of the bravery and essential morale-boosting work that a group of largely forgotten female entertainers embodied during a national crisis.